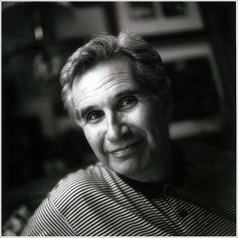

By David Finkle | davidfinkle.com

FOREWORD

In presenting the following manuscript, I’m asking you, the reader, to recognize as true a series of (almost entirely) serendipitous incidents that will strain credulity to the breaking point and possibly far beyond it, as far beyond as the other side of the grave.

I ask you to take my word that what are included here are no more nor less than events experienced by myself and others over several years. The others are men who trusted me with their accounts after they had learned of mine.

I have to confess that I never recorded the.men’s stories as I listened attentively. I only relay them as I remember them—as accurately as possible, to be sure. They are too indelible to be forgotten. They are absolutely not the sort of unexpected happenstances I—or they—would have been able to concoct out of whole cloth. I am not convinced that anyone could, though others might deem it possible.

Nevertheless, without further explanation, here the manuscript is for your perusal. Whether or not you believe what you read is not up to me—any more than what I maintain as occurring in the first place was, or is, a matter of my volition or those whom I represent.

I also ask that, if you choose to reject what you’re about to read as a series of impossibilities in the world you know—or think you know—please withhold your scorn and simply dismiss the accounts as fantasies dreamed up in the kind of fertile mind I only wish I had.

–Paul Engler

August, 2014

Ted Prentiss’s Story, or Jane Austen Meets Her Match in Three Minutes

“I might establish a dating service,” Jane Austen said to me, a guy who’s always had trouble approaching women, “but then again, it is just an idle thought.”

Yes, it’s that Jane Austen speaking, the Jane Austen.

Why shouldn’t she be? She had every right to, and I had every right to respond, whatever my romantic history—or lack of it. Not only that, but she wasn’t proving to be noticeably modulated in her address, as I might have expected she would be. Her speech was clipped, close attention paid to final consonants. Her tone was emphatic, though not all the way to harsh.

To be exact, I was registering this shortly after we had embarked on an entertaining exchange at the Barnes & Noble branch on Manhattan’s Union Square. I was there looking for—then at and on—the Paul Auster shelf, or partial shelf, which ought satisfactorily to explain: (1) that I wasn’t there looking for Jane Austen or thinking about her at all, and (2) why I had to make my way around a woman in a smocked dress and delicate tea-cozy-like cap as I worked along alphabetically.

If I weren’t the type of person who has to know what other people are reading or contemplating reading (that I could recommend or recommend against), I might not have even noticed Miss Austen as anything other than someone standing between me and my destination.

But I am that type. Since it’s easier for me to bury my nose in a book rather than go out on Saturday night, talking about books is just about the only situation in which I’d start a conversation with a woman.

So when I’d found the Austers—but before removing the one I wanted from the row of them—I cast a sidelong glance at what the person to my left was reaching for and saw it was Pride and Prejudice.

Thinking to be witty, I said to her even while not yet looking squarely at her in my reticent fashion, “It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune—” (Just to be clear, I’m a single man but not in possession of a good fortune.)

But before I finished quoting, she stopped me in my verbal tracks. Standing as tall as she could, which wasn’t tall at all, and fixing me with penetrating hazel eyes, she said, “I do not intend to be rude, Sir, but I find no satisfaction in being quoted back to myself. By now I have heard myself quoted far too many times to consider it refreshing or droll.”

That is an attention-getting remark, of course, and caused me to take a closer look at the woman. I saw someone who resembled drawings of Jane Austen I’d seen, wearing clothes resembling clothes she might have worn.

I thought to myself, however, that someone told she looked like Jane Austen—or even had she not been told she looked like Jane Austen—could undoubtedly find more than one Manhattan boutique where eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century outfits with contemporary tweaks might be purchased. Any woman wanting the Laura Ashley appearance can have it. There still are Laura Ashley outlets, aren’t there? Maybe there aren’t anymore.

“Funny,” I said, “you do remind me of what I think Jane Austen looked like. You’ve certainly captured the period.”

“There is a simple explanation for that,” she said, while avoiding contractions and methodically adjusting one of the curls peeking from under her dainty cap and then returning to the book she’d pulled out. “I am Jane Austen. Though you may have difficulty believing me, I see no reason to deny it.”

I must have been looking doubtful, because she added, “I see you do not believe me, but here I am and not by choice. I am here by force. They grew tired of my complaining.”

At that, my expression must have shifted to completely befuddled.

“It seems my constant complaints about how my writings have been travestied over the years caused untold vexation among the others.” She pointed a gloved right forefinger upward. “I was sent here to do my fulminating where it might have an effect. Here where authors have been commissioned to finish my unfinished scribblings. Where authors have been commissioned to write books in my style. Where authors have been commissioned to write uncalled-for sequels and, for all I know, what are called ‘prequels,’ to my few humble novels. Frankly, I’m not interested in Elizabeth Bennet as a child or a suburban matron.”

Chagrin crossed her face like clouds covering the Royal Crescent at Bath. “Do you know there are even books in which I have been appropriated as a character? More than once as a common detective? You can imagine how humiliating that is.”

Not being Jane Austen, I wasn’t convinced I could imagine how humiliating that is, but I nodded as if I could and said, “I can tell you I occasionally write fiction, but in your case I would never deign to be that presumptuous.”

“Then you’re one of the few,” she said and slapped the book she held against her free palm. “Do you know that Pride and Prejudice has even been turned into a comic book?” She put the words “comic book” into verbal italics, as if she found the phrase belittling—humiliating—and would never have used it in any other context.

She accompanied the italics with the sort of face-distorting expression you make when you’ve just swallowed something unexpectedly sour. It made her handsome (rather than pretty) face a thing of no great appeal.

“I did not know that,” I said, hoping the emphasis I put on “not” evidenced at least a modicum of sympathy and polite horror. On the other hand, I was thinking I would like to see a Pride and Prejudice comic book. I figured that would indeed be something to behold.

She said, “The residents of the other realm were tired of hearing these sorts of diatribes.” She waved her arm vaguely in several directions. The shawl she had arranged over her shoulders stirred slightly. “So here I am,” she said, “looking at my own books to confirm that they remain intact, that they’re not sullied as a result of the treatment accorded them for so long now, and counting.”

She fixed me with a look as if—despite my denial—I could be the next literary pirate, or perhaps she was regarding me as a convenient stand-in for whomever might be the next ungrateful poacher. I tried to look as innocent as I could of clod-like trespassing on intellectual property.

She patted me on my large hand with her small gloved one and said, “You must forgive me. Already you see how hot-tempered I become on the unbecoming subject. Where I have lately been, anything excessively hot is sent packing, at least temporarily. But now that I’ve ascertained my books are safe in themselves, perhaps I can relax.”

I said I thought that might be a worthwhile idea.

“As you may know,” she ventured, “relaxation in Bath where I spent the years eighteen hundred one through eighteen hundred five was frequently done at the spa or in the assembly rooms. I see no spa here, nor do I see anything resembling an assembly room.”

We were walking out of the Austen-Auster aisle, and she was gazing around. By then, I’d completely forgotten why I was there, and said, as I looked down the escalator at the level immediately below, “Perhaps I do see something reminiscent of an assembly room.”

She followed my gaze and, getting a glimpse of the café, saw where many book-buyers had—well—assembled. She said, “So it does. Perhaps you’ll join me for tea.

Tea with a figment? I don’t think so. Tea with an actual living-and-breathing person? Why not? I said, “I would be delighted, Miss Austen.”

“And you are…?” she said, extending a gloved hand again.

“Oh,” I said—shaking the proffered hand and noting it might be small but the grip was as strong as her grip on consonants—“I’m Ted Prentiss. Theodore.”

“Mr. Prentiss,” she said. “Normally, I wait to be introduced, but I know no one here to introduce us.”

I nodded my understanding in what I realize now was how I thought an early nineteenth-century gentleman might nod. Had I been wearing a hat, I probably would have tipped it. (I wasn’t and how kempt my hair appeared was questionable.)

So began our tete-a-tete—her tete, bonnet-covered; my tete, uncovered—and it wasn’t long before she made the remark about launching (my word, not hers) a dating service.

Over our herbal (the “h” is pronounced) teas, for which I insisted paying, we’d been talking about what she might do while back this side of the eternal divide. Since she’d returned, she said, she’d had enough time to conclude she couldn’t put a stop to the writing that traded on her name, but she’d also come to understand that she was here for the duration, which meant she was here until she made some contribution or other or attained some goal—she wasn’t certain which or what.

Since she seemed to be looking for suggestions, I—never at a loss for suggestions—made a few. The several I came up with, however, she’d already considered and rejected.

The most obvious, almost needless to say, was writing more novels. About that possibility, she was brisk, even brusque. “I’ve said what I had to say,” she said. “I might have completed Sanditon while I’m here, but, as you may know, it has already been unceremoniously finished for me.”

With little pause, she said, “And I will not be launching a detective service, as some of the fabulists have had me do. Stuff and nonsense. If I poke into people’s lives, it is not the sordid aspects. It is decidedly not a universal truth that people with a murder case to be solved are in need of Jane Austen. I examined lives from an entirely different perspective, which I would have considered something I need not explain.”

Whenever she finished a statement about herself, Miss Austen—I wouldn’t have dared address her by her given name, nor did she address me by mine—had a habit of aiming at me, and perhaps anyone with whom she was conversing, a direct gaze. It was as if she was challenging me, or whomever, to challenge her.

I wasn’t inclined to do so but instead considered a few more suggestions.

While I was deciding which one to mention first, she made her dating-service remark—“I might establish a dating service, but then again, it is just an idle thought.”

“Not a bad one,” I said, wondering how she’d come to know such things existed as an outgrowth of nineteenth-century match-making. “Dating services are big now, especially online—if you know what that is.” As someone so reluctant to date, I don’t know why I was going on like this.

She nodded that she did know and gave the notion some thought while looking around the room. I saw her gaze light on the murals placed high on the Barnes & Noble café walls. In them are depicted caricatures of famous authors as if taking tea together, or something stronger, at the same watering hole. Among them are Virginia Woolf, Mark Twain and William Faulkner. Not among them is Jane Austen.

Nothing in her expression indicated her reaction to the playfully contrived mural. She merely shook her head—so that the curls appearing from under her bonnet stirred placidly—and addressed the idea of a dating service. “I do not think so. I was able to arrange matches in my fiction. I even had Emma Woodhouse come a cropper at the endeavor, but in life it is a different matter.” For a moment, her eyes lost their shine. “At the dating game, I never did well for myself, did I?”

She seemed to be asking that of herself rather than of me. So I remained mum about both her hard romantic luck—and mine—and changed the subject by saying, “What about writing a book on manners? That’s something we have a great big lack of these days.”

She tilted her head in thought and crossed her feet in front of her. I hadn’t noticed this before, but she was wearing delicate-looking slippers with flowers embroidered on the instep.

Before she could respond to the book on manners idea, I said, “Or if you don’t want to write, you might want to establish a finishing school for independent young women who nevertheless like the idea of honoring traditions thrown out with the bath water—no pun intended—during the early feminist movement years.”

“Yes, the feminist movement,” she mused. “I have heard of that. Discussing where it went wrong, Betty Friedan has alienated almost as many of the others up there as I have. I’m surprised I do not see her here as well.” She looked around in what I took to be jest and then held the position for an instant, while slowly saying, “Or that contentious Andrea Dworkin.”

Turning to face me again, Miss Austen hesitated for what I’d estimate was no more than another split second. It was long enough, though, for me to wonder what had caught her obviously keen eye. I looked in that direction, too.

I saw a man approaching us. Not us, exactly, but looking for a place near us. There were a few available tables and chairs, and he was clearly aiming to sit at one of them.

He was, to put it in a word, handsome. In two words—one hyphenated—he was what no one in an Austen novel would have called “drop-dead handsome.” In twenty-five words or more, he was tall, had wavy hair, a bold jaw and an athletic gait. He had a prominent nose of the kind not thought of as refined enough for the twenty-first century but would have been more than acceptable in a Joshua Reynolds or Thomas Gainsborough portrait. He was wearing clothes designed to look simultaneously expensive and subtle—a tweed jacket I imagined came from Ralph Lauren’s Seventy-second Street mansion as might have the gabardine slacks, lawn-green cashmere sweater and suede slip-ons. No, the shoes could have been bespoke—Jermyn Street, John Lobb, perhaps.

Looking close enough to my image of Fitzwilliam Darcy and perhaps to Miss Austen’s image as well, he was holding a book. As he got near, I could see it was—of all unlikely tomes—Sir Walter Scott’s Guy Mannering.

Guy Mannering was published in 1815, two years before Jane Austen originally died. So Miss Austen would have been aware of the best-selling Sir Walter Scott—who in his poem, “Marmion,” wrote “O, what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive!” And Sir Walter Scott would have been aware of her. (Don’t ask how I know any of this, but English majors sometimes retain relatively useless information.)

Whether Miss Austen had been able to discern the title of the book the man was carrying our way I can’t say, since aside from the quick-as-a-hummingbird’s-wing hesitation, she had returned to our conversation and was not looking at anything or anyone but me.

Nevertheless, I had no doubt she was aware of the man. Nor did I doubt she was aware I’d caught her fleeting notice of him. She gave nothing away, nor did she allow that she paid any special attention to him when he stopped at the table next to us and asked in a chamois voice that sounded as if it could have belonged to a wee-hours radio deejay, “Do you know if anyone is sitting here?”

There was no evidence that anyone had previously staked out the table—no folded newspaper, no book or books, no coffee cup or plate with a partially eaten biscotto on it, no reading glasses, nothing.

If I could tell as much, so could he. I let it ride and answered, because it was clear Miss Austen wasn’t about to, “Doesn’t look that way.”

I’m saying I answered. I’m not saying he looked at me while I said it. He was looking at the silent Miss Austen, who happened to be directing her gaze somewhere in the middle distance and below mural level.

“Well,” the Sir Walter Scott reader said and pulled one of the chairs out, “if someone is sitting here, I can always move when he or she returns.”

That remark—which did have something in it of the inane—prompted Miss Austen to say, without shifting her attention, “That is true. You can always move.”

I admit I’m frequently slow on the uptake. It’s been a lifelong problem. But the tone in Miss Austen’s voice—cooler even than she had heretofore been in our chat—hipped me that something was up. I guessed it was connected to this third party but also felt I didn’t know her nearly well enough to ask what was bothering her, if “bother” was the correct assessment.

In any case, I didn’t get the opportunity to ask because we were again interrupted by the newcomer at the next table. “Do either of you know anything about this book?” he asked, holding up Guy Mannering.

Before I could respond, Miss Austen said, “He’s a fine writer,” then paused for only a second, before adding, “if you have a fondness for that kind of book.”

I could tell she meant her answer to be a conversation stopper, but I could see in the gentleman’s ice-blue eyes that he had more to say. Ignoring her curt comment, he said, “I picked it out, because I’ve always liked the name Guy.”

I’ll just throw in here that none of this was meant for my ears. For all intents and purposes, I didn’t exist for this fellow.

I didn’t hold much interest for Miss Austen at that moment, either, although their reasons for dismissing me were, from what I could tell, diametrically opposed: He was trying to engage her, and she was immersed in trying to disengage from him.

Neither was having much success.

“An affinity for the name Guy seems a questionable reason for selecting a book with which you plan to spend valuable time,” Miss Austen said, again visibly—to me at least—intending to end the byplay.

He said, “I beg to differ, Ms.—” and shifted from leaning towards us (towards her; I was wallpaper) to sitting upright and squaring his broad shoulders. “Forgive me. I don’t know your name.”

“Miss Austen,” she said, not, evidently, wanting to be rude, “Miss Jane Austen.”

He put out his hand, leaving her nothing to do but shake it, and repeated, “Miss Jane Austen.” He cocked his head and got a gleam in his eye. He said again, “Miss Jane Austen. Like the novelist.”

“Yes,” Miss Austen said, “exactly like the nineteenth-century novelist.”

“Never read her,” he said. I gulped audibly. To myself at least. “She’s girl—er—women stuff, what they call ‘chicklit,’ I think. I suppose you have. Read her, that is.”

“In a manner of speaking,” Miss Austen said.

“Is she as good as they say?” he asked.

She replied, remaining cool as a cucumber, “I am not really in a position to opine.”

“Doesn’t matter,” he said. “What matters at the moment is I’m Guy Hudson.” He laughed so that his teeth took on the brightness of a digital billboard advertisement. “Yes, you’re right, Miss Jane Austen. My name in a title is a poor excuse for reading a book.”

He swiveled the Guy Mannering copy he held back and forth as if the heft of it might somehow reveal its quality to him or us. “You seem to know it, too. Are you recommending I don’t read it?”

Miss Austen took a second or three to ponder the question. What I took to be mild disdain crossed her face. If that’s what it was, I couldn’t discern whether it was disdain for Sir Walter Scott or Guy Hudson or both, although if I had to choose, I’d say it was the third option.

She seemed to have taken a dislike to Mr. Hudson but said in crisp, neutral tones, “I am not in the habit of recommending or not recommending books, Mr. Hudson, and if you do not mind—”

He cut her off. “But I do mind. Please call me Guy.”

“Mr. Hudson,” she repeated, and I could tell she was not the sort of person who brooks interruptions kindly. (Far as I could remember, no one in her books interrupts anyone else—and that includes Mr. Bennet when harangued by Mrs. Bennet.)

“You have your book,” Miss Austen went on. “If I were to recommend anything, I would recommend your reading a few pages of it to see for yourself whether you might take joy in it. And now if you do not mind, I would like to return to the conversation I am having with my friend.”

Hudson took that in and said with a certain amount of hurt but also defiance in his piercing eyes, “I’m sorry to have disturbed you. I won’t do it again.” He turned away from us and opened the book, intently paging to, I suppose, the first chapter. He began reading with showy concentration.

Miss Austen didn’t wait for that to happen. She sought to resume whatever we’d been discussing. “Where were we?” she asked but not without an hauteur I took to be residue from what had just transpired.

Where had we been? Good question. I had to think. Oh, yes, we’d been talking about the contribution she needed to make—whatever that was—before she could go back where she’d come from.

I was just about to remind her where we were, when we heard a silken voice from the next table.

“I know I said I wouldn’t disturb you again, Miss Austen,” Mr. Hudson said, “but I feel I must ask you if I have offended you in any way. If I have, I’d like to know what it is I need to apologize for doing?”

Miss Austen took time with her answer, while both Hudson and I waited to see what she’d say. “No, Mr. Hudson,” she replied, “you have not offended me, but—”

Again Hudson jumped in. “Then if I haven’t offended you,” he said and his chest seemed to swell with the news, “I don’t see why we can’t talk—”

Need I repeat it was as if I had altogether vanished into a convenient void?

This time Miss Austen cut him off by saying—and again with somewhat chilly attitude—“I was about to say, Mr. Hudson, that you have not offended me, but if you continue in this way, you will be offending me. You seem not to honor my talking with a friend but rather think yourself deserving of preferential attention.”

“Then you do have something against me, Miss Austen,” he declared.

Had I just heard what I’d just heard? It was as if I were hit by a thunderbolt of recognition. Miss Austen had just accused Mr. Hudson of pride, and Mr. Hudson had just accused Miss Austen of prejudice. I’d landed smack-dab in the middle of a life-imitates-art pot of jam!—practically a life-imitates-art slice of life! As an inveterate reader, all I had to do to entertain myself with nearly surreal pleasure was see how the situation played out.

Hold on. I was due to meet friends—honest-to-goodness friends—at seven, but what I was witnessing could present a problem. Would I have enough time to see the battle of wits before me through to the end? If the contents of Miss Austen’s acclaimed works had established a precedent, this could take months, and—I checked my watch while they eyed each other—I only had about two and a half hours.

Just then the most marvelous thing happened, something that made me realize once and for all how times change and with them how old traditions can wither and fade—even if they’ve been embedded in the tangy aspic of early nineteenth-century print.

Guy Hudson said to Jane Austen, “I’m going to propose something to you, Ms. Austen.”

“That remains Miss Austen to you,” Miss Austen said.

“Welcome to the twenty-first century,” Hudson said, meaning to be funny.

Jane Austen turned my way with an if-he-only-knew-the-whole-of-it look.

“You know about speed dating, I’m sure,” he said to her and didn’t wait for an answer, he was that certain she did know. “I’m going to propose we do a little speed-dating run right here. Why?” He didn’t wait for an answer then, either. “Because you’re an attractive woman, and I’m an attractive man, and I think we ought to get to know each other.”

“You are being uncommonly audacious, Mr. Hudson,” Miss Austen said.

“I’m only asking for three minutes of your time,” he said, holding up his left hand, palm out. It made me think that were I to get a glimpse of his nails, I’d see they were well-manicured. “If after three minutes you can say you don’t want to see anything more of me, I promise to take my Guy Mannering and disappear from your life forever.”

Again, he waved the book in the air.

Jane Austen thought that over. “You have broken one promise to me already,” she said. “How do I know you will not break this one?”

Hudson tilted his square jaw thirty degrees higher and said, “Because this time I give you my word as a gentleman. What do you say?” With his right hand, he pulled his left jacket sleeve back and the sleeve of his sweater and went about removing his watch. He handed it to me.

“Your friend will time us,” he said. He didn’t look at me when he said it, but that gesture was at least an acknowledgment that I was present.

“If three minutes will purchase my freedom from you,” Miss Austen said, “then I agree to the challenge. It seems a small price to pay.”

I was thinking about the price of the watch I now had in my possession. It was a Rolex Submariner I clocked at between seven and ten thousand dollars. That wasn’t, of course, such a small price to pay.

“We’ll begin on my count of three,” Hudson said, still not looking at me but fixing Miss Austen with a roguish expression. “One,” he said with anticipation, paused before saying “two” and took a longer pause before saying “three.”

Since I was looking at the Rolex, I noted that his “three” resounded just as the second hand passed the twelve: This Guy guy was all perfection.

As I kept an eye on the Rolex’s second hand and an ear on the give-and-take, I regretted that I had no tape recorder with me with which to capture what I was hearing. That’s to say, I can’t recall what was said verbatim. I can only give you an approximation of what was said, but, trust me, it’s a reliable approximation of all the fervor and urgency to which I was privy, as they say in Morocco-bound novels.

Here goes:

Hudson: I’m pleased to make your acquaintance, Miss Austen, but even though you’ve denied as much, I believe I have offended you. I will admit I can do that with women to whom I’m attracted. I suppose it’s a character flaw, and I have many, I’m sure. On the other hand, I have always known what I want and have felt it serves no purpose not to act quickly on it. Anything else is a waste of time, and if I have any strong dislikes, it’s anyone or anything that wastes my time or anyone else’s. To that end, I made my first million before I was twenty. I founded a dot-com company that remained solvent during the first dot-com bubble burst.

Austen: Mr. Hudson, I am someone to whom a single man in possession of a good fortune means less than it might to other women. On the contrary, I believe that a man who refers to his fortune before his less demonstrable qualities is a man whose motives are to be questioned. Perhaps it is a bias, but it is one from which I have always profited. I believe that one must live by standards and strict ones at that, although I am aware that my position can be interpreted by others as unforgiving.

Hudson: If you’ll forgive me, Miss Austen—I won’t presume to call you Jane—I think it necessary to devote some time to the reasons why men and women do what they do and not judge them simply by first impressions. I find that impulse a sign of weakness. I mentioned my success in business for two reasons. The first is that it means I am a man with whom a woman can feel secure—not, incidentally, in a nineteenth-century way but in a more contemporary manner. My equity allows me to encourage a woman with whom I’m involved to pursue her own interests. The second reason is that I believe in philanthropy and, without calling attention to myself personally—a condition I deplore—I’m able to do something about my beliefs with some humanitarian gestures about which I shall go into no further detail.

Austen: Were I to take you on faith, Mister Hudson, I would have to confess I may have misjudged you, but I would also have to say my attitudes, should they seem aloof, have not sprung full-blown from my maiden’s mind and heart. They have been formed in response to the ways of the world I have seen around me and the responses to me of that often misguided world. I have often been misjudged myself but, I think to my credit, have never greeted misjudgment with anything but humor. I am prepared to cede, however, that what strikes me as humorous may not always show on my face. Perhaps that is a flaw of my own.

Hudson: I commend you on your confession, Miss Austen. Conceding flaws isn’t common to many women of my acquaintance, I have to say. The women I know may carry on about various features on their faces that they’d like rectified by expensive plastic surgeons, but that’s their faces. They never apologize for their expressions.

Austen: For my part, Mister Hudson, I know of too few men who understand that humanitarian obligations might possibly take precedence over the attentions they pay to their own person. I do, on the other hand, admire your taste in apparel.

Hudson: Same here, Miss Austen. I like what you’re wearing, too. It’s maybe more demure than I usually go for, but I have to say the joining of soft clothes with a tough mind is a winning combination.

Just as Hudson, uttered the phrase “winning combination” and inhaled more deeply than he had for the length of the Austen-Hudson exercise, the Rolex second hand crossed the three-minute mark.

“Three minutes,” I said with a staccato tempo picked up from them.

Not that they noticed me, only the signal to stop I’d announced.

They ceased talking but remained looking at each other. Guy Hudson’s strategy had worked. They had gotten through to each other—had qualified as “a winning combination.” But were they thinking what I was thinking: What do they do now?

I imagined Hudson expected Miss Austen and he would go off to dinner somewhere or just take a walk or possibly a ride in whatever sleek vehicle he had parked somewhere nearby. But that couldn’t be what Miss Austen expected, could it? Given the little I knew of her, it wasn’t what I imagined she’d do.

Finally, Hudson spoke just as Miss Austen opened her mouth to say something. They both laughed, and it was laughter that had what I can only call a merry ring to it.

Drawing on what I took to be turn-of-the-eighteenth-century deferral, Miss Austen signaled to Hudson that he should speak first.

He did but not without an appreciative nod. “Perhaps we can talk further and at a more leisurely pace elsewhere,” he said. Then he looked my way for only the second or third time and added, “If your friend doesn’t mind.”

Caught off-guard, I made a few awkward shakes of my head to let him and her know I didn’t mind. If I had minded, what difference would it have made?

At my diffident nod, Hudson rose and offered his hand to Miss Austen, who stood and said to me, “It’s been a pleasure, Mr. Prentiss.”

I sputtered, “For me as well, and one I hope to repeat.”

“One never knows,” she said and joined Hudson, who had moved off a few steps.

They turned then and walked away but not before Miss Austen looked back at me while I was still within earshot and said, “I think I know why I am here now.”

Then they proceeded to the escalator. As they stepped onto it, I saw him reach for her gloved hand. She didn’t let him take it. Instead she slipped her arm through his.

They descended.

I’m sorry to say that what happened after that, I have no way of knowing. When they disappeared from my view, did they vanish completely? For all I know, they might have. Did Jane Austen leave behind anything to serve as a reminder of her brief drop-by in my life? No. The only thing left behind was on the table Hudson had occupied: the paperback copy of Sir Walter Scott’s Guy Mannering.

I chuckled to myself that just as Jane Austen had eclipsed Scott for readers at the beginning of the nineteenth century, she’d just done so again at the brightening dawn of the twenty-first.

Did Miss Austen evaporate from Hudson’s life as mysteriously as she materialized in mine? Did the two of them try a relationship that didn’t work out, as so many don’t? Are Miss Austen and Mister Hudson living together in the connubial bliss denied her during her (previous) lifetime?

I can’t say. What I can say is that a young woman—an attractive one at that—approached the table on which Guy Mannering lay. She looked at it, turned to me and said, “Is someone sitting here?”

“No,” I said. “I guess the guy who brought it over before he left a minute or so ago decided not to buy it. I don’t see why you can’t sit there.”

Whereupon she sat down, and we started a conversation—a conversation we’ve often continued. She reads. She likes books. She doesn’t seem to be on the hunt for a single man in possession of a good fortune.

DAVID FINKLE is a New York-based writer who concentrates on the arts. He writes regularly on theater, books, music and fashion for The Clyde Fitch Report, The Huffington Post, and The Village Voice. He’s contributed to scores of publications, including The New York Times, The New York Post, The Nation, The New Yorker, New York, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and American Theatre. He also writes short stories and novels.